Explorer Elise Wortley’s new documentary charts life of Henriette d’Angeville (10 March 1794) the second woman to climb Mont Blanc and the first to do so unaided

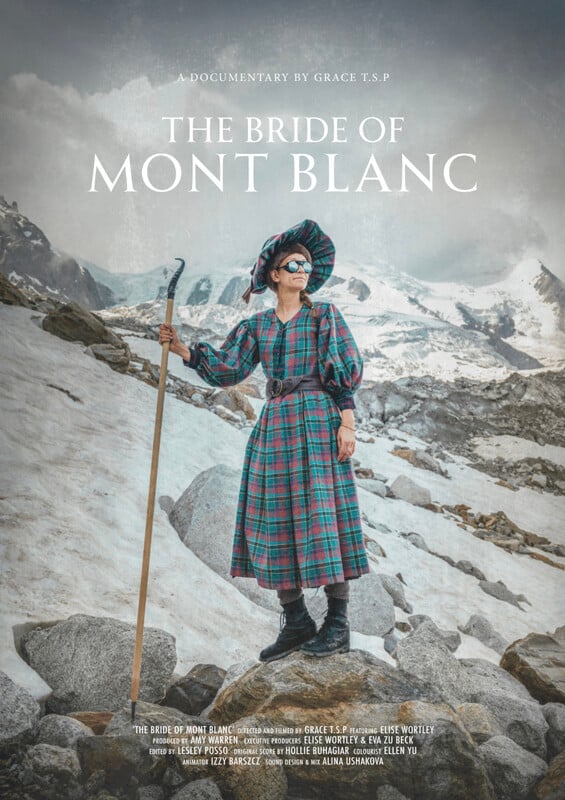

By the time the morning sun flares over Chamonix, the first thing you notice about Elise Wortley is the wool. Thick, hand-stitched, 1830s wool: petticoats layered beneath bloomers, a heavy bodice, a bonnet softened by the touch of her mother’s hands. It is utterly at odds with the slick neon shells flashing around her on the trail, but that’s precisely the point.

For centuries, the world of exploration has been dominated -at least in public memory, by the image of the fearless male adventurer.

But hidden beneath the stories of famous men are countless women whose courage, curiosity and defiance shaped the history of travel and discovery. These were women who crossed continents when society barely allowed them to walk alone; who climbed mountains before trousers for women were socially acceptable; who documented cultures, mapped remote regions, and pursued knowledge with unwavering determination.

Known by her friends as Lise, is a runner-up on ITV’s Alone!, has made it her mission to make sure we don’t forget them telling HERstory rather than HIStory.

Since her early twenties, Elise has been painstakingly retracing the expeditions of overlooked women adventurers-following their routes, facing their challenges, and even wearing the same clothing and equipment they would have used. By immersing herself so literally into their journeys, she hopes to reclaim these women’s stories, challenge modern stereotypes of adventurers, and support women working in the outdoor space today.

Her most ambitious mission yet has been an attempt to climb Mont Blanc dressed entirely in hand-made 1800s clothing -bloomers, bonnet, wool, petticoats and all -exactly as Henriette did when she became the first woman to make the ascent unaided in 1838.

For centuries, our cultural imagination of exploration has been dominated by images of rugged, fearless men battling the elements. Yet beneath that familiar narrative lie lesser-known stories -women who trekked across continents, climbed mountains, and pursued knowledge, often under far more restrictive conditions. Elise is determined to bring those stories into the light.

Her mission is simple, but radical: retrace the expeditions of forgotten women explorers, using only the clothing, kit and mindset they had available.A timely spotlight:

The Bride of Mont Blanc

Elise’s journey has gained powerful resonance with the recent release of the short documentary The Bride of Mont Blanc, directed by Grace T.S.P. The film, completed in September 2025, follows Elise as she dons period gear and attempts the climb, exploring not just the physical challenge, but the emotional, historical, and feminist dimensions of reviving Henriette’s ascent.

At just 27 minutes long, the documentary is itself a labour of reclamation – produced by an all-female crew, from director and guiding team to post-production. Its very existence amplifies Elise’s mission: to restore visibility to women whose mountaineering achievements have been eclipsed, both in history and in present-day culture.

The documentary has already been screened at international festivals, including a showing at the Transylvania Mountain Festival. A public screening and Q&A was also held in London in November 2025, giving audiences a chance to hear directly from Elise, the director, and fellow mountaineers about the significance of this project.

The story of Henriette d’Angeville

The film’s title, The Bride of Mont Blanc, directly nods to Henriette d’Angeville, often called by that very epithet. In climbing circles and historical accounts, she is remembered as the “Bride of Mont Blanc” – not because of marriage, but for her deep, spiritual devotion to the mountain itself.

In an era when women’s independence was constrained by both social norms and practical limitations, especially in clothing.

Henriette wrote her own chapter in mountaineering history. She crafted her own outfit out of heavy wool, engineered for survival rather than style, and tackled the mountain with a small team of guides. By retracing that ascent, Elise resurrects not just the physical act, but the emotional and symbolic one: Henriette’s love for the high places, her bravery, and her challenge to expectations.

Elise’s Climb: Beyond the physical ascent

When Elise set out to recreate Henriette’s climb, she didn’t just don a costume, she committed to the full historical experience. The wool she uses comes from the Scottish Borders, mirroring the kind of material available in the 1830s. Her outfit’s colours are based on a period book cataloguing 19th-century fabrics.

She’s supported by a close-knit, mostly female team: her guide Karen, with over thirty years’ experience on Mont Blanc, and Grace, the filmmaker, among others. “It’s a community,” Elise says: makers, seamstresses, shoemakers and historians coming together to resurrect a forgotten story. The climb itself, however, was halted due to dangerous rockfall and the risks posed by melting ice.

Elise acknowledges that the mountain has changed since Henriette’s day – and so has the climate. The rocks are more unstable, the ice less predictable. But for Elise, the preparation, the research, and the lived experience of wearing period gear are every bit as valuable as summiting.

A story of healing, anxiety, and identity

One of the most compelling threads in The Bride of Mont Blanc is Elise’s own internal journey. She has spoken openly about her struggles with anxiety, and how nature – especially wild, remote places – provides a kind of sanctuary.

Climbing Mont Blanc in 19th-century clothing becomes, for her, an act of emotional excavation: wearing Henriette’s clothes, carrying her mindset, and confronting her own fears.The act of walking in hobnail boots, or navigating high passes in a heavy wool skirt, forces Elise to slow down, to feel the discomfort, to reckon with what being a 19th-century female climber would actually have been like. It’s not romanticism: it’s empathy through immersion.

She describes channelling Henriette, but not pretending to be her. It’s less reenactment, more conversation across time.

Reclaiming women’s place in the outdoors

This project, and the documentary that celebrates it, are not just about historical curiosity. They speak to ongoing, systemic issues in the outdoor world – gender inequity, lack of representation, and the narrative that “real adventurers” are men in gore-tex gear.

Elise has long argued that the mountains, the wild places, are for everyone – not just for men, and not just for those who already fit a certain mould.Her commitment to hiring women, training with women, celebrating women both past and present, makes the project itself a statement. The Bride of Mont Blanc amplifies that statement, bringing Elise’s physical, emotional, and symbolic climb to audiences who may never trek to 4,800 metres – but who can be inspired to rethink who belongs in the story of exploration.

The spark that started it all

Elise’s fascination with forgotten women explorers began at sixteen, when she stumbled upon a book by Alexandra David-Neel, the first Western woman to meet the Dalai Lama and a pioneering explorer of Asia. In 1910, as an unmarried woman defying every societal expectation, Alexandra embarked on a fourteen-year journey across the Himalayas—sleeping in the snow, learning from monks, and delving deeply into the world of Buddhism.

“I couldn’t understand why I had never heard of her,” Elise recalls. “She was extraordinary.

Why wasn’t she part of my education?”

The more she searched, the more she realised how routine it was for women adventurers to be sidelined by history, their stories dwarfed by their male counterparts. That discovery became the foundation of her project.

When she was in her mid-twenties, Elise retraced a portion of David-Neel’s route through India, relying only on traditional clothing and materials—yak wool, handmade shoes, and a simple pack, sourced through friends and artisans.“

I wanted to understand the barriers these women faced, even down to how uncomfortable their underwear might have been in 1907,” she says. “And the deeper I went, the more their experiences came to life.”

Following Henriette D’Angelo up Mont Blanc

Henriette D’Angelo’s 1838 ascent of Mont Blanc reads like a piece of fiction. With no appropriate women’s clothing available at the time, she designed and stitched her own wool climbing outfit -twelve kilograms of fabric that defied both weather and gender norms. She trekked with six male porters who carried roast chickens, veal, mutton, wine, prunes, chocolate, lemons, and cognac.

Elise laughs: “I’m vegetarian—well, I eat fish now after Alone -so Karen, my guide, can have the chicken. But I am taking the flagon of lemonade and barley water. And the blancmange.”

Sourcing authentic clothing is always a challenge. For this climb, Elise used Scottish Borders wool just as Henriette did. Without photographs, only greyscale drawings, she searched for a book cataloguing the clothing colours of the 1830s and handed the palette to her mother, who stitched the outfit by hand.

My mum made it. Someone else made the underwear. Another woman made the shoes. It’s this beautiful community effort -like a village.”

Her team on the mountain also reflects her mission: all women when possible. Her guide, Karen, has been climbing Mont Blanc for three decades, and filmmaker Grace documents every step.“I always try to hire female guides. The outdoor industry is still very male. Even in Europe, most guides on Mont Blanc are men.”

Despite meticulous preparations, the Mont Blanc attempt was cut short due to dangerous rockfall and unpredictable weather caused by rapidly melting ice. But for Elise, the training, research and connection to Henriette were just as vital as reaching the summit.

Immersing herself in history and confronting modern fearsElise’s expeditions aren’t just physical -they are emotional, technical, and psychological undertakings. She often trains for months, hiking across UK national parks and spending hours on step machines despite her longstanding anxiety around gyms.“I had a panic attack in a gym ten years ago. But now I’m finally comfortable going back. That’s progress to me.”

Walking into a crowded Alpine hut in full 1830s dress, however, still terrifies her.“Everyone else will be in high-tech gear, and I’ll be in a bonnet. All the heads will turn. That’s scarier than the climb.”

The fear is real, but so is her resolve. Elise works hard not to let discomfort overshadow the truth she’s trying to understand: the resilience of the women who came before her.“

I don’t pretend to be them. But I try to channel them. I get to know them inside-out by literally following in their footsteps.”

A life shaped by adventure

Outside her expeditions, Elise works in PR in London for the ski-holiday company Inghams, juggling corporate life with historical mountaineering. She spends her free time hiking, surfing, practicing yoga, or planning her next mission.

She has now completed expeditions in Scotland, India, Iran and other regions—though her time filming Alone remains one of her profound experiences.“I was in the wilderness for 34 days. My eyesight got sharper, my hearing better. I knew what time the geese would fly over. I became completely wild. It was beautiful.”

Her Iran expedition, retracing the journey of explorer Freya Stark, also stands out. She describes Iran as completely different from its portrayal in Western media -warm, welcoming and full of strong women.“

Freya Stark was like a female Indiana Jones, mapping places no one in the West had seen. I found the valley she mapped—the Valley of the Assassins. No one had walked that path since before the 1970s revolution.”

Looking ahead to the next forgotten heroineElise has a long wish list of women whose journeys she dreams of retracing. Among them is Grace O’Malley, the sixteenth-century Irish pirate queen who met with Queen Elizabeth I. Elise imagines recreating O’Malley’s voyage with a boat full of women dressed in sixteenth-century pirate clothing, but the cost of building a historically accurate galleon puts the project at around £80,000.Another dream project: explorer Annie Smith Peck, a suffragette and mountaineer who planted a “Votes for Women” flag atop the highest volcano in South America.

And beyond these famous names, Elise hopes to highlight women from across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East -voices made even harder to find due to historical erasure.“

I don’t know if I’m the right person to dress as them or retrace their steps, but I’d love to work with women from those communities and bring their stories forward.”What’s next – and why it matters now.

The release of The Bride of Mont Blanc feels like a moment of reckoning. As climate change reshapes mountains and mountainside communities, as the outdoor industry begins to grapple (slowly) with inclusion, Elise’s work reminds us that history is not fixed. Women’s stories were lost, minimised or forgotten – but they can be rediscovered.

Meanwhile, The Bride of Mont Blanc invites viewers to witness the resurrection of a narrative. It’s not just a film about climbing a mountain – it’s a reclamation, a call to action, a tribute.

In retracing Henriette’s steps, Elise Wortley doesn’t just climb Mont Blanc — she raises her voice on behalf of hundreds of women whose names we are only now beginning to remember. And in doing so, she invites us all to imagine new possibilities for who gets to be an adventurer.

The power of nature – and community

Anxiety has been a part of Elise’s life, but nature has always been her antidote.“When I’m in nature, I don’t have panic attacks. My mind goes quiet. Everything slows down. That’s why I keep doing this.”

She also finds strength in the community she’s built: craftspeople, historians, mountaineers, followers on Instagram, fellow explorers and the women whose paths she retraces.

“I’m humbled by the people I’ve met. I’m planning a big dinner for everyone who’s helped me out forty people. They won’t all fit in my flat!”

As she works on her first book and continues recording her expeditions in hopes of creating a documentary, Elise remains committed to her mission: making sure the world remembers these women and inspiring the next generation of girls to chase adventure.“

There’s still no female Bear Grylls,” she says. “But maybe the girls I meet in schools will become the women who change that.”

I met Lise when she invited me to a press trip in Zermatt and I was so inspired by her story.

Leave a comment